Video By: Sharaz Sikander | Article By: Alankrita Anand

According to the Health Ministry, 61% of the Primary Health Centres (PHC) in the country function with only one doctor and almost 8% with none. Ideally, each PHC should have a minimum of two doctors along with three nurses, a lab technician and a pharmacist. The on-ground reality, however, cuts a sorry picture.

This World Health Day, at a time when the government is floating health insurance schemes like Modicare, we take a look at one of the smallest units of India’s public health system– the Sub-Health Centre or the SHC.

Community Correspondent Sharaz Sikander visited a Sub-Health Centre in the border district of Poonch in Jammu. The Centre, located in a hilly area, caters to villages under two panchayats (village councils); in real numbers, this is a ratio of one SHC to 40,000 people. The story is not very different in other parts of Poonch, where until four years ago, health centres were functioning from private homes and shops, and needless to say, were unstaffed and understocked in crucial drugs.

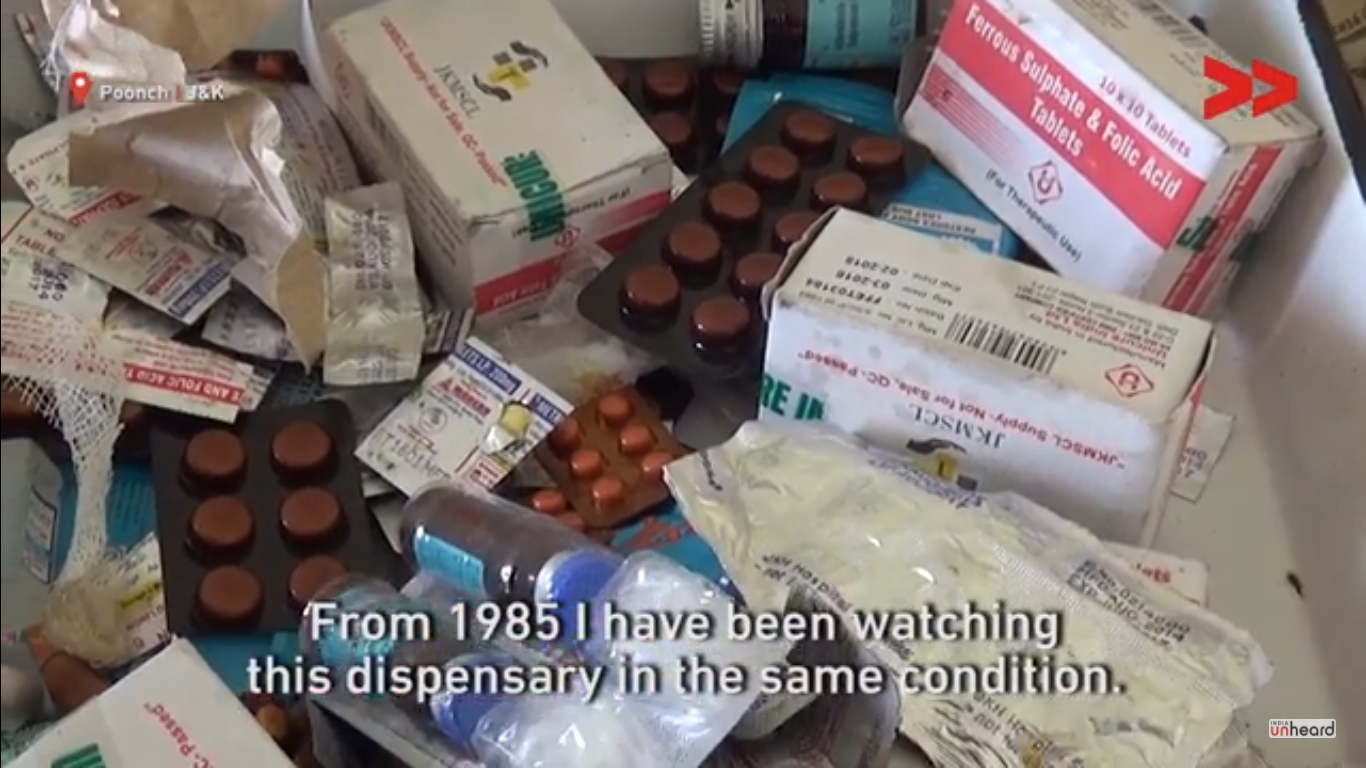

Poonch, with a population of 4.77 lakh people has only 143 public health centres, of which 96 and Sub-Health Centres. But even when there is a proper SHC building, it may not serve its purpose when there are no proper drugs. What is worse is that the Centre in Banpat, which Sharaz visited, has not had electricity since it was built in 1985.

“How will we store vaccines properly without a refrigerator?” asks Mohammad Qasim, a resident of Banpat. One of the main purposes an SHC is expected to serve is to provide immunisation facilities for children and pregnant women. A study from Chhattisgarh shows how crucial power is to rural healthcare.

SHCs are of two types- Type A which is supposed to have all facilities (OPD and immunisation) except labour rooms and Type B which is supposed to have a labour room as well. The SHC in Banpat does have the basic physical infrastructure required for a Type B centre, but it does not have the facilities required for institutional delivery, or the necessary equipment or drugs.

The Jammu & Kashmir has plans to upgrade 2,800 SHCs in the state but no such work has happened in the areas of Poonch that Sharaz visited.

“The lack of institutional delivery facilities is the biggest problem that the residents of Banpat face”, says Sharaz. He says that the SHC is in one end of Banpat, closer to the urban centre of Poonch, but the residents of the area, which is spread over hills, stay in far-flung places. “There are no ambulance services either and hiring a car to go to the nearest Primary Health Centre or to the hospital is a nightmare”, he adds.

“We have to put the patient on a charpoy (makeshift stretcher) to get them to the main road and then look for a car there,” says Mohammad Ayub, another resident of Banpat.

When Sharaz visited the Chief Medical Officer (CMO) of Poonch, he received a twisted response. “The CMO asked me to see the good work that his department is doing in the urban parts of Poonch, and then shift my focus on the rural parts. But in urban areas, people have access to and can afford private healthcare as well, so the government needs to focus on rural health services,” he says. Sharaz is now following up with the CMO on the progress of the work in the SHC in Banpat.